Iridescent Networks, Inc. v. AT&T Mobility, LLC

Patent claim terms which have relative meanings might not be easily defined and may cause problems for enforcement. As will all claim terms, these terms will be defined in light of the language an applicant uses in the specification, as well as arguments an applicant makes during prosecution. Accordingly, care should be taken during prosecution to tailor arguments carefully so as not to unduly limit claims. These principles are illustrated in a case decided by the Federal Circuit this week.

On appeal, AT&T prevailed against Iridescent Network, who sued AT&T for infringing U.S. Patent No. 8,036,119. Claim 1 of the’ 119 patent recites:

1. A method for providing bandwidth on demand comprising:

receiving, by a controller positioned in a network, a request for a high quality of service connection supporting any one of a plurality of one-way and two-way traffic types between an originating end-point and a terminating end-point, wherein the request comes from the originating end-point and includes at least one of a requested amount of bandwidth and a codec….

Ironically, AT&T succeeded in arguing that its services were not infringing because they were not “high quality.”

That an applicant may define terms in her own patent is a key tenet of patent drafting. If a term in the claims has a clear, ordinary and customary meaning among practitioners in the relevant art, the term will be accorded its accepted meaning. Conversely, where there is no such customary meaning, a claim term will is defined based on the prosecution history of the patent.

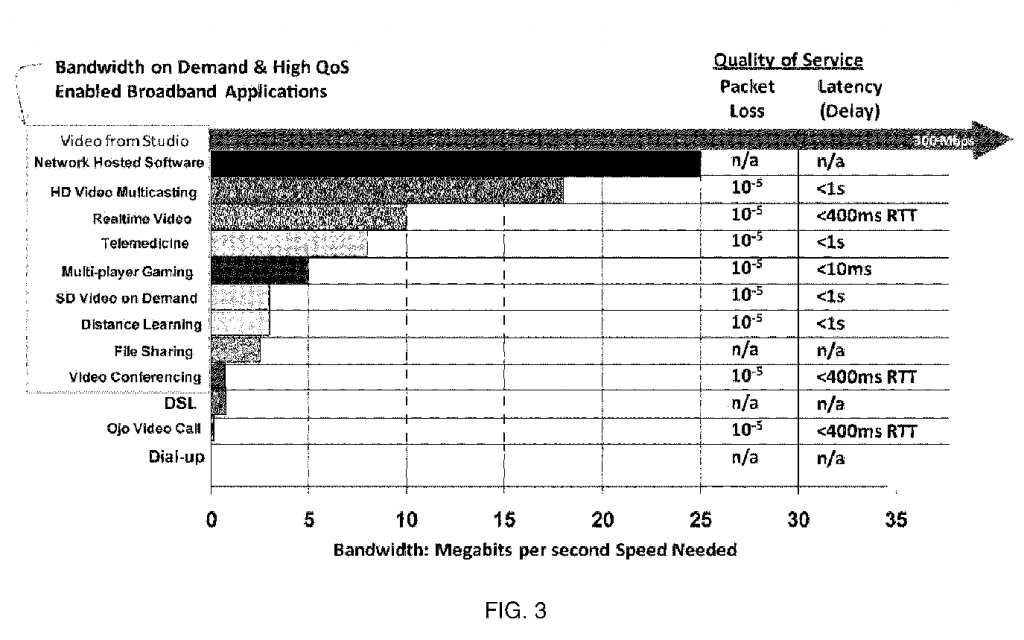

Care must be taken when defining terms, both during patent drafting and prosecution. Although “high quality” was not explicitly defined in the text of the patent, a chart was included in the patent as FIG. 3, which differentiated various services by quality in terms of speed, packet loss and latency.

During prosecution the Examiner rejected the claims as lacking enablement. In particular, the Examiner asserted that the term “high quality” was not defined and that the specification “d[id] not adequately describe how high quality and low latency are determined.” In response, Iridescent cited FIG. 3 and argued that the parameters for “high quality service” were defined as having speeds of about 1-300 Mbps, packet loss of about 10-5, and latency of less than one second. FIG. 3 clearly identifies high quality of service (“High QoS”) applications in FIG. 3 as those which are boxed on the left-hand side. The Examiner subsequently allowed the application.

Iridescent argued on appeal that “high quality” simply means “assured quality,” which is a term that was used throughout the specification. The Court was unpersuaded, noting that the decision to claim a connection providing “high” quality of service as opposed to “assured” quality would indicate to a person of skill in the art that the claims require something above and beyond mere quality assurance.

The Court limited the meaning of “high quality of service” to speeds varying from about 1-300 Mbps, packet loss requirements that are about 10-5, and latency requirements that are typically less than one second, as set forth during prosecution. The Court reasoned that Iridescent’s statements made during prosecution “focuse[d] on the objective characteristics of the quality of the connection rather than on whether any amount of quality is assured.” Iridescent’s arguments during prosecution pointed to very particular parameters illustrated in FIG. 3.

Because AT&T’s service did not fall within the above parameters, the Federal Circuit held on appeal that it was not a “high quality service” as that term is used in claim 1 of the ‘119 patent.

Patent practitioners should take note that arguments made during prosecution may supplement the patent disclosure for purposes of defining and limiting terms.